Cockerell’s first great benefactor was Charles Brinsley Marlay. Educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge, he was a wealthy bachelor with considerable estates in Ireland and a large London house, which he filled with an extensive art collection. He was a member of the Burlington Fine Arts Club and Cockerell met him through the manuscript exhibition he organised there in 1908.

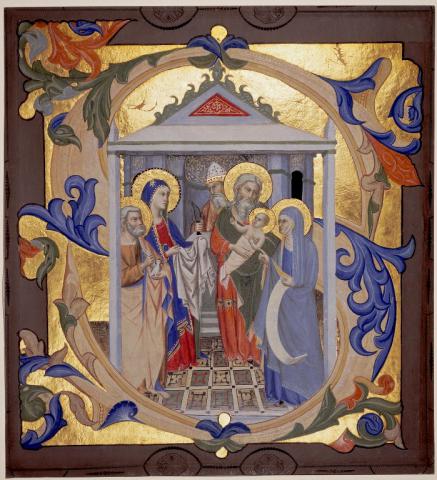

Marlay lent some of his manuscripts to Cockerell’s exhibition and in 1912 bequeathed all of them, eighteen volumes and 240 illuminated cuttings, to the Fitzwilliam Museum. Marlay’s cuttings dated from the twelfth to the sixteenth centuries and represented every major school of medieval and Renaissance illumination.

They were the product of two intimately related phenomena of the early nineteenth century, the awakening interest in ‘the lost art of illumination’ and the destruction of manuscripts in the wake of the Napoleonic campaigns in Italy and the secularisation of religious houses across Europe. The realisation that far more medieval painting survived between the covers of manuscripts than on panels or walls, stimulated the cutting up of volumes and the disposal of the main body of text.

The miniatures were preserved as ‘the monuments of a lost art’ and framed like small panels, providing collectors with examples of medieval painting in greater quantity and superior condition. Marlay’s collection of cuttings, one of the largest in private hands, included exquisite leaves from Books of Hours and from the celebrated Choirbooks of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Florence, San Marco in Venice, and the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican.

In July 1908, within a month of his arrival in Cambridge, Cockerell called on Marlay

‘to talk to him about an addition to the Fitzwilliam.’

Marlay was keen to leave his large collection to the Fitzwilliam and Cockerell argued that he needed ‘money to build a gallery to house it.’ Marlay offered £50,000, but the Director insisted: ‘What about staff?’ Marlay promised another £30,000 and the lease of his London house. Cockerell was content:

‘It was I who landed this big fish.’

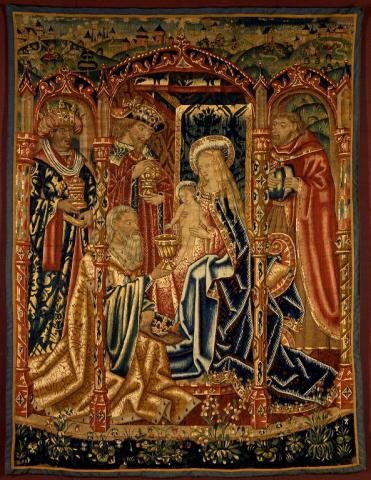

Marlay’s bequest allowed him to undertake his first building campaign and brought to the Museum an astonishing variety of objects in addition to the illuminated manuscripts and cuttings: paintings, prints and drawings, rare books and precious bindings, European and Oriental pottery and weapons, silver, bronzes, glass, ivories, enamels, jewellery, Japanese lacquer and netsuke, furniture, carpets, and tapestries. Demonstrating Marlay’s taste for the opulent and highly ornate, the collection contained works of great beauty, such as the Tournai tapestry with The Adoration of the Magi of c.1500 or the contemporary Venetian tazza with the lion of St Mark. However, it also included second-rate objects and even some of dubious authenticity. Marlay was, in Cockerell’s words, a ‘bargain-hunter.’

As soon as the bequest was officially accepted, the Director mounted a campaign for the disposal of any objects that were ‘modern, imitation, or of too low standard for an important museum.’ Although criticised for this drastic action, Cockerell created a much-needed purchase fund for the Fitzwilliam.