Cockerell’s interest in antiquities, first aroused in the 1880s by Philip Webb, developed fully upon his arrival at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

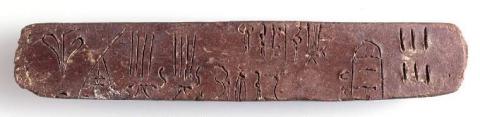

By 1910 he had made important purchases and was clearing space for the display of the Greek vases. In 1911 he announced a special gift from Sir Arthur Evans, a clay tablet of c. 1375 BC found in the Palace of Minos at Knossos and inscribed in the Linear B script used by the Mycenaeans c. 1550-1200 BC, which Michael Ventris and John Chadwick would decipher in 1953.

The bequest of Charles Brinsley Marlay brought more treasures in 1912 and created a purchase fund. In 1913 Cockerell appointed the first Honorary Keeper of Greek and Roman Antiquities, F.H. Marshall. His successor was Miss Winifred Lamb. Cockerell met her in 1918 when they crossed swords in the saleroom. Impressed by her knowledge, passion and acumen, the Director offered her the Honorary Keepership. Miss Lamb held it until 1958, becoming a generous benefactor and raising the profile of the collections through groundbreaking research, acquisitions and publications.

Cockerell was anxious about the authenticity of acquisitions. A laudatory account of his directorship published in the Times upon his retirement in 1937 referred to Wilhelm Bode’s purchase of a wax bust of Flora ‘from the atelier of Leonardo’ that turned out to be a fake and warned that ‘every museum director had a wax bust waiting for him at the end of a passage.’

The columnist praised Cockerell whose ‘wax bust is waiting still.’ In fact, it was already at the Fitzwilliam. In 1926 the Museum had paid a colossal £2750 for what was thought to be ‘the earliest Greek marble statuette in existence’, dating to c. 1600 BC and representing a Cretan goddess. Cockerell consulted specialists at the British, Ashmolean and Victoria and Albert Museums, who confirmed its authenticity. Sir Arthur Evans hailed the statuette as a masterpiece of the recently discovered Minoan civilization.

‘There is no doubt about its genuineness,’

he told Cockerell,

‘but… I doubt even an American millionaire collector would give Seltman’s price.’

Winifred Lamb advanced half of the sum and Dr Glaisher encouraged the Director:

‘I do not think we could spend the Marlay money better.’

A year after the purchase Cockerell visited the Cretan Museum at Candia and was told that the statuette was made by a former member of staff. Her close relations, other ‘Minoan goddesses’, were flooding the art market. Eventually, it was established that all were the work of two Greeks employed by Sir Arthur Evans to restore his finds in Crete.

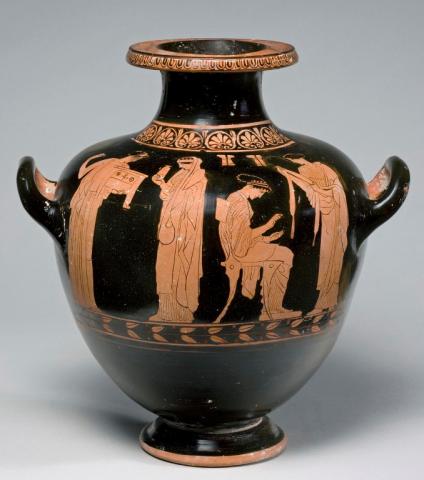

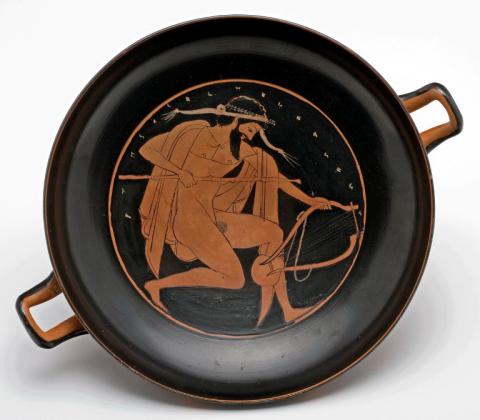

Cockerell and Miss Lamb enriched the holdings of Greek and Roman antiquities thanks to the Marlay Fund, the subscriptions of the Friends of the Fitzwilliam Museum, the Antiquities Purchase Fund that they raised together and the generosity of private sponsors, including Mr and Mrs Chester Beatty and Miss Sydney René Courtauld. The single, most important collection of antiquities arrived at the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1937. Formed by Cockerell’s old friends, Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon, it had first come on loan in 1933 and the Director knew that it would ‘remain permanently in Cambridge.’

Among the Egyptian, Greek and Roman artefacts were Tanagra statuettes, classical gems, Greek vases and sculpture, including the exquisite marble bust of Antinous, Hadrian’s handsome and ill-fated lover who drowned in the Nile in 130 AD. Charles Shannon left all of these treasures to the Museum on his death in March 1937, just a few months before Cockerell’s retirement.