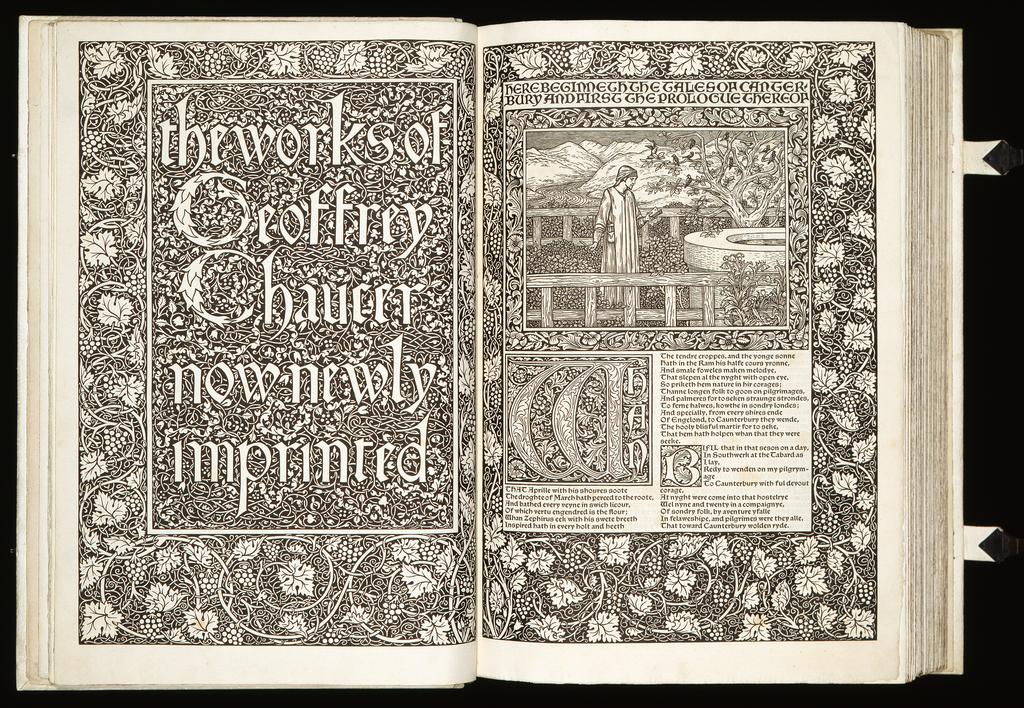

In July 1894 Cockerell was appointed Secretary of the Kelmscott Press, William Morris’s last great enterprise launched in 1891. It inspired the setting up of other Private Presses and led to the unprecedented revival of fine printing and book design around 1900. The majority of the 65 titles published by the Kelmscott Press were written, translated or edited by William Morris in five years, between 1891 and his death in 1896. All were set in types and embellished with ornamental initials and borders designed by Morris himself, a prodigious output characteristic of his energy and devotion to his projects. The woodcut illustrations were prepared after designs by Morris’s friend and collaborator, Edward Burne-Jones.

Morris’s crowning achievement as a book designer was the Kelmscott Chaucer. The first copies arrived on 2 June 1896. Morris was on his deathbed and asked Cockerell to take over the Kelmscott Press together with Emery Walker, the typographer who had contributed so much to the success of the Press. Cockerell declined, arguing that the standards of craftsmanship set up by the great man could not be sustained and the Press ‘would fizzle out by degrees.’ As one of Morris’s executors, Cockerell oversaw the completion of the last Kelmscott books, sold the stock, and wound up the Press on 31 March 1898. He was content:

‘the Kelmscott Press… came triumphantly to an end about a week after March 24th, William Morris’s birthday, on which the last two books were issued.’

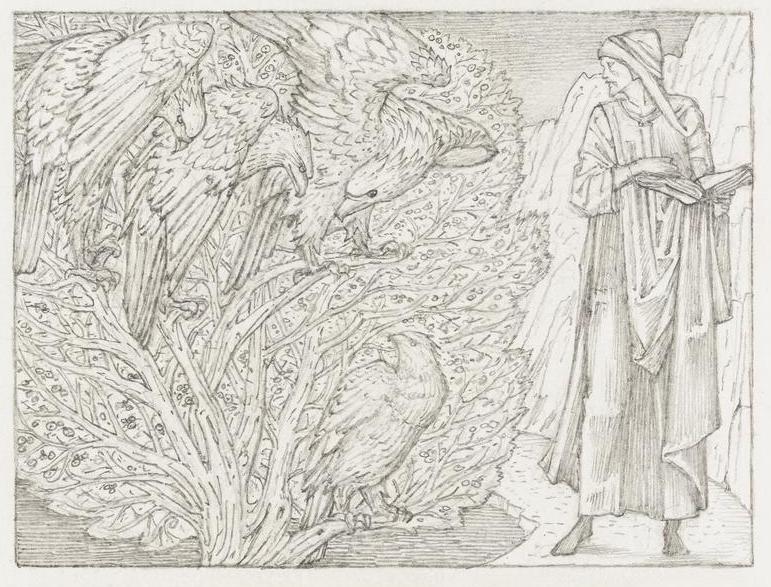

Cockerell was determined to acquire a complete set of Morris’s books for the Fitzwilliam Museum. The Kelmscott Chaucer, which he coveted most, was the ‘principal feature’ in the display of books printed on vellum that Cockerell arranged in the Central Gallery (Gallery 3) in 1918. He had convinced Emery Walker to lend his copy. In 1921 the Museum received 87 of Burne-Jones’s highly finished drawings for the Kelmscott Chaucer’s woodcut illustrations from Stanley Baldwin, the former Prime Minister and nephew of Lady Burne-Jones who was to become Chancellor of Cambridge University in 1930.

Cockerell borrowed another vellum copy of the Chaucer, this time from Cambridge University Library, in order to display it together with the designs. In 1922 he purchased Burne-Jones’s preliminary studies for the Chaucer drawings from the Friends’ Fund. In 1930 Morris’s elder daughter Jenny lent the Kelmscott Chaucer together with her entire set of Kelmscott books - ‘complete except for four items,’ rejoiced Cockerell. Thirty-six of them bore the inscriptions William Morris had penned as he presented the books to his daughter. Cockerell offered Jenny much comfort and practical support throughout her long illness. Upon her death in 1935 she bequeathed her 62 volumes to the Fitzwilliam.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898)

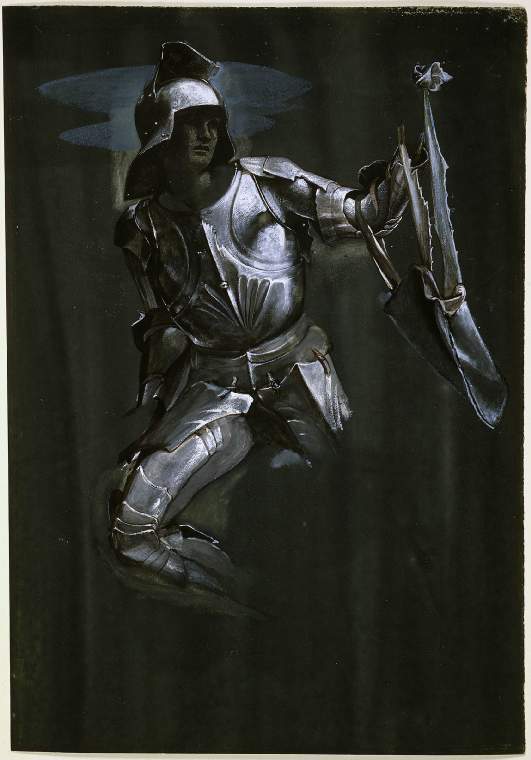

Cockerell met Edward Burne-Jones on 30 November 1890 and began visiting him in his studio at The Grange, the artist’s London house in Fulham. On 30 December 1896 he watched him paint Perseus and the Graiae, the last of only four designs for the Perseus series to be completed in oil. This study of Perseus for The Finding of Medusa was presented to the Fitzwilliam Musem by the artist’s widow and children in 1909, within a year of Cockerell’s arrival.

Cockerell’s loyalty to Morris and his family had drawn him close to Burne-Jones and his wife Giorgiana, who were eager to show their gratitude.

‘There is nothing in the world that I would not do for you in return for your goodness to him,’

Burne-Jones had told Cockerell by Morris’s deathbed. Cockerell was a frequent visitor at The Grange and at the Burne-Joneses’ holiday home in Rottingdean, outside Brighton. He enjoyed a warm friendship with Burne-Jones’s daughter, Margaret, and her husband, J.W. Mackail, whom he helped write Morris’s biography published in 1899. Margaret and her brother Philip would leave some of Burne-Jones’s sketchbooks and his entire archive to the Fitzwilliam Museum.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882)

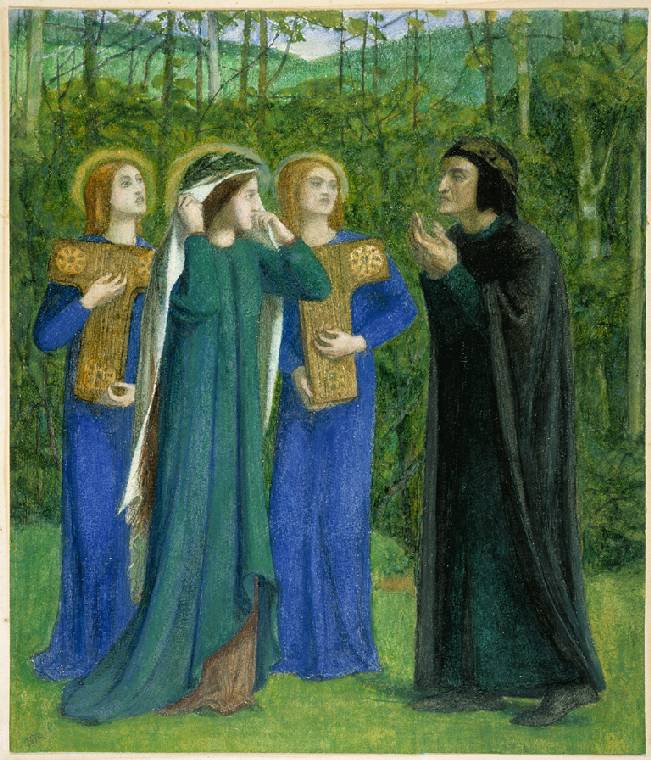

As a private collector Cockerell is best known for the medieval and Renaissance illuminated manuscripts that he gathered through his unrivalled knowledge of the field and the trade. But his collection also contained Pre-Raphaelite works. He bought a stained glass cartoon by Ford Madox Brown in 1893 and in 1898 acquired his first drawing by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. In 1900 Philip Webb made him a special Christmas gift, Rossetti’s Dante and Beatrice meeting in Purgatory. Cockerell had first caught sight of it on 28 August 1890 when he called on Webb and ‘saw an amazingly beautiful early Rossetti drawing of the meeting of Dante and Beatrice.’

Based on the Vita nuova, which Rosetti had translated in 1848, the year when the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded, this depiction of Dante’s heavenly reunion with Beatrice is a witness to Dante’s powerful influence over Rossetti’s visual and poetic works. Verses from the Vita nuova are inscribed on the frame, one of the earliest extant examples of frames treated by Rossetti as organic parts of his works. While his entire career was dominated by the fusion of poetry and the visual arts, this watercolour represents his early or ‘medieval’ period inspired by illuminated manuscripts and by the poetry of Dante and Sir Thomas Malory.

It was in the 1850s that Rossetti met William Morris and Burne-Jones, who embraced his Arthurian themes for the frescos at the Oxford Student Union. Rossetti painted another subject inspired by the Vita nuova, The Salutation of Beatrice, for the Red House completed to Philip Webb’s design for William and Jane Morris in 1860. Cockerell visited the Red House in 1891 and was impressed by the frescoes, stained glass, tiles, and furniture ‘by different members of the old Morris-Webb-Rossetti company.’ Philip Webb gave him this drawing on the condition, inscribed on the back of the panel, ‘that, when he had to dispose of it, the picture would finally be placed by him in a National English Gallery of Paintings.’ While honouring his promise to Webb, Cockerell favoured his own Museum. Rossetti’s watercolour was his retirement gift in 1937.

Rossetti’s last painting, Joan of Arc harks back to the medieval themes of his early watercolours, but its medium, style, composition and scale are markedly different. The rich oils, the fiery and lustrous effect, the dramatic close-up, the sumptuous masses of red hair and the opulent drapery characterize the sensuous half-length female portraits of Rossetti’s last period. Found on the artist’s easel upon his death in 1882, Joan of Arc was acquired by Charles Fairfax Murray.

A studio assistant of Rossetti, William Morris and Burne-Jones, Murray had ‘made himself happy in the background’ in the 1870s. But by the early 1890s when Cockerell met him Murray had acquired an enviable reputation as an expert on the Old Masters and the Pre-Raphaelites, as a collector, connoisseur, dealer and adviser to private and public collections.

After Burne-Jones’s death Murray took over his studio at The Grange and, sitting on his hoards of Pre-Raphaelite material, became the most knowledgeable and jealous guardian of the artists’ legacy. He consulted Cockerell on the disposal of his medieval manuscripts and in 1905 offered thirty of them to the Fitzwilliam. He supplemented them with autographs by Rossetti, Morris and William Blake, hoping to encourage Cambridge to develop a collection of literary and artistic autographs. This happened only after Cockerell’s arrival when Charles Fairfax Murray became one of the Fitzwilliam’s most generous and demanding patrons. Joan of Arc was among his first gifts presented in 1909. Among the last, offered in 1918 by a grateful Murray who received much help from Cockerell during the last years of his life, were Rossetti’s sofa and one of the Fitzwilliam’s most famous paintings, Titian’s Tarquin and Lucretia.