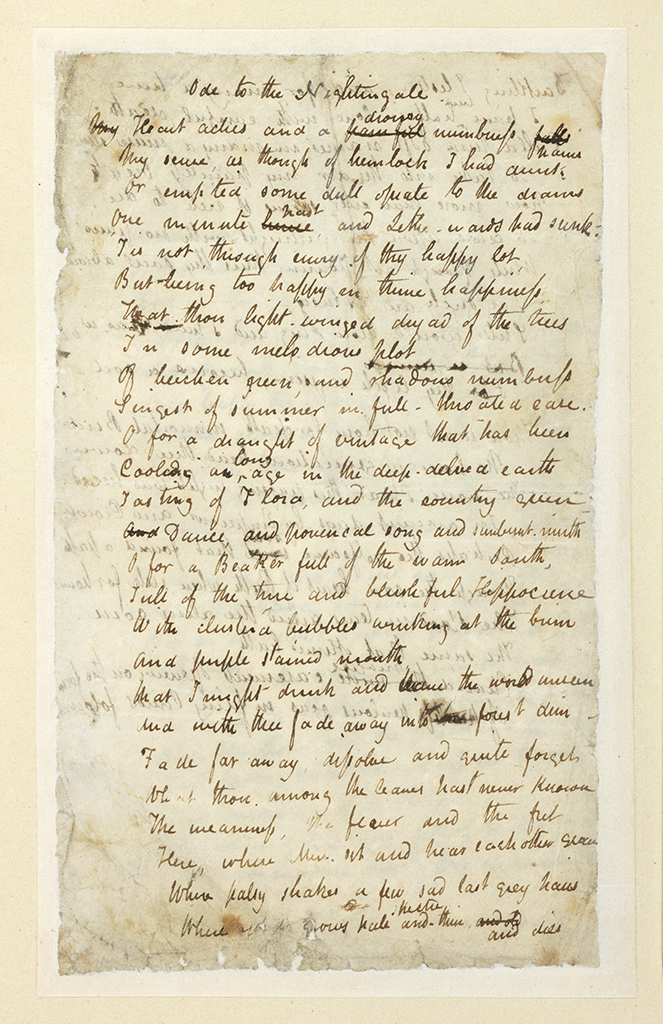

Keats’ friend and house-mate, Charles Armitage Brown, recalled how the poet sat in his garden in Hampstead on a beautiful May morning in 1819 and, moved by the ‘tranquil and continual joy’ in the song of a nightingale nesting nearby, wrote the lyrics within a few hours. Embellished as this account may be, the hastily penned lines recapture a moment of spontaneous creativity as experienced by one of the greatest Romantic poets.

The lyrics were published in July 1819 with a slightly altered title, Ode to a Nightingale, and became one of the best-loved poems ever composed in the English language. When the original manuscript came up for sale in 1901, Sidney Colvin, Keats’ biographer and former Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum, urged the Marquess of Crewe to buy it and keep it in this country: ‘it is a shabby enough little ms. to look at, but of almost unequalled literary interest.’

Having exerted a powerful influence on the Pre-Raphaelites, especially on Rossetti and Morris, Keats’ poems were among the special editions of the Kelmscott Press. As he was winding up the Press in 1898, Cockerell remarked that they were ‘the most sought after of all the smaller Kelmscott books.’ A decade later he would read his favourite poet to Florence Kate Kingsford during their courtship and honeymoon. While visiting Mrs Furneaux in Oxford on 26 October 1907, Cockerell admired two drawings of Keats made by her father, the painter Joseph Severn who had nursed the dying poet in Rome in 1821. In 1911Cockerell secured for the Fitzwilliam the portrait of Keats that Joseph Severn had painted for the poet’s beloved, Fanny Brawne. It was bequeathed by Charles W. Dilke whose father had built the house in Hampstead where Keats met Fanny and wrote Ode to the Nightingale. Keats was buried with a lock of Fanny’s hair. In 1920 J. Pierpont Morgan presented a lock of Keats’ hair that Joseph Severn had cut off on the poet’s deathbed and Cockerell had it enclosed within the frame of the portrait. In 1932 he persuaded the Marquess of Crewe to lend his autograph of Ode to the Nightingale to the Fitzwilliam Museum and within a year the loan was transformed into a permanent gift. Cockerell rejoiced: ‘This great treasure is exhibited in Gallery V and will always be regarded by lovers of poetry as one of the principal attractions of the Museum.’

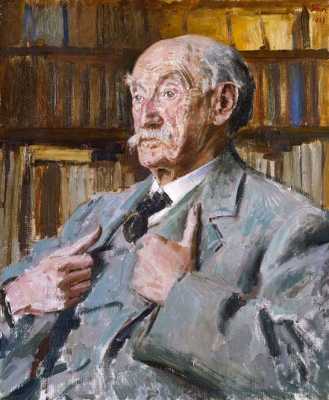

Thomas Hardy (1840-1928)

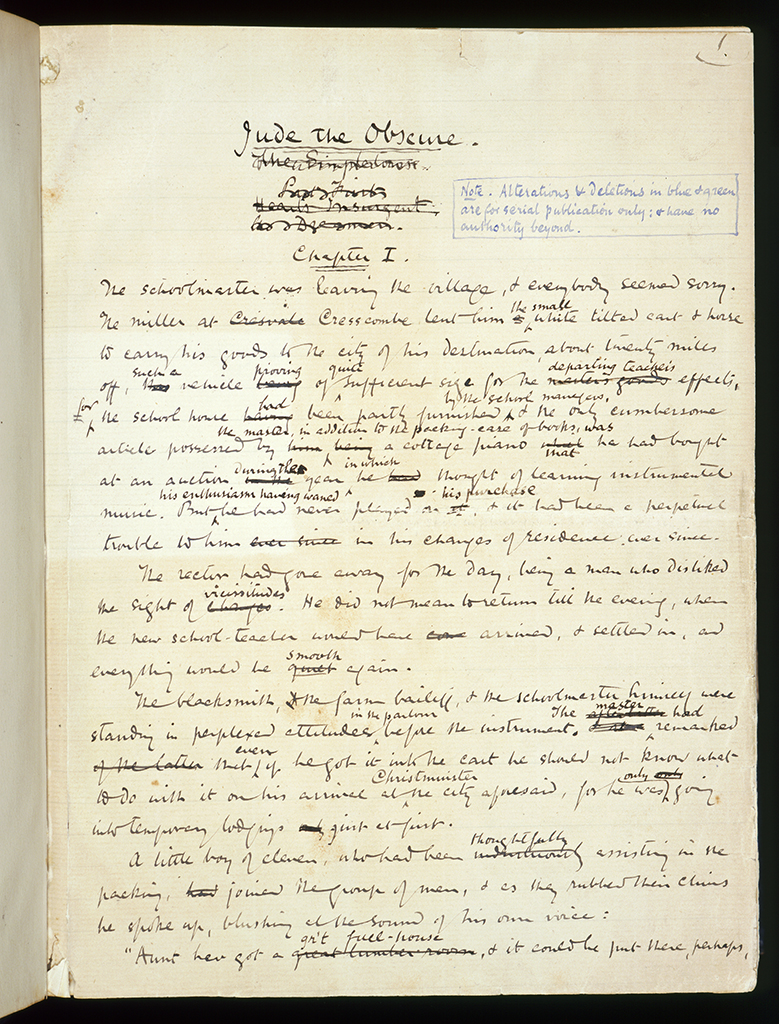

Cockerell set himself the task to create a collection of literary manuscripts unique in the context of fine art museums. In 1911 he wrote to Thomas Hardy asking him to ‘give one of his manuscripts to the Fitzwilliam.’ They had never met and Cockerell had not yet read any of Hardy’s works, but he was invited to Max Gate, Hardy’s ‘modern villa’ outside Dorchester. ‘He received me most kindly and I spent a couple of hours with him talking about Morris, architecture etc.,’ wrote Cockerell in his diary. ‘He asked me to undertake the distribution of his manuscripts and after he had shown me what he had got I divided them between the British Museum, Cambridge, Oxford, Aberdeen (which had given him a degree), Birmingham, Manchester, Dorchester, Windsor and Boston or New York and arranged to write to the various curators and librarians as he felt a delicacy about doing so.’ For the Fitzwilliam Cockerell chose the autographs of Hardy’s most celebrated novel, Jude the Obscure, and his 1911 collection of poems, Times’ Laughingstock.

Cockerell ensured that the University, to which Hardy had dreamed of applying as a young man, recognized his generosity and mounted a campaign for an honorary degree. Hardy received it in 1913 and was also offered an Honorary Fellowship at Magdalene College. Cockerell became a regular guest at Max Gate, and a close friend and confidant of both Thomas Hardy and his second wife, Florence Dugdale. On 16 February 1922 he noted with pride: ‘T. Hardy paid me the compliment of sending me a long introduction for his new volume of poems for my opinion.’ By then he had read all of Hardy’s works.

Having secured Hardy’s autographs, Cockerell felt the urge to acquire a good portrait of the author as well. In 1912 the Friends of the Fitzwilliam Museum purchased a drawing of Hardy by William Strang and in 1919 they paid for an etching, also by Strang. In 1923 Augustus John completed a dignified portrait of the eighty-three-year-old Hardy, surrounded by his books and absorbed in his thoughts, but still alert and curious about the world. Cockerell persuaded his friend and patron, Thomas Henry Riches, to buy it for the Fitzwilliam.

Jude the Obscure has iconic status in the history of English literature. A key example of the so-called New Fiction, the transitional stage in the development of the English novel between the Victorian and the modern era, it is representative of the fin de siècle aesthetics and anxieties. It charts the fateful struggle of individuals following their intellectual aspirations against human nature, social hypocrisy, and life’s adversities. In the author’s own words, this is a story ‘of a deadly war waged between flesh and spirit’. He saw Jude the Obscure as the greatest among his ‘novels of character and environment’.

Thomas Hardy was forced to make numerous changes for the serial publication of Jude the Obscure which appeared between December 1894 and November 1895 lest the family-based audience of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine’s be scandalized. He inserted all changes in blue or green ink in the manuscript, leaving the original text perfectly legible and adding the note: ‘Alterations and deletions in blue and green are for the serial publication only and have no authority beyond.’ Hardy’s autograph is displayed here for the first time after a comprehensive conservation campaign funded by the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust and completed this summer by Svetlana Taylor.

The first book edition of Jude the Obscure to be published by Osgood, McIlvaine and Co. presented Hardy with the opportunity to restore the original text and elaborate on it. When it appeared in 1896 it challenged traditional views on class, education, religion, love, sex, and marriage. The critics were shocked and accused Hardy of ‘immorality’. He gave up fiction and for the remaining thirty years of his life wrote only poetry. Jude the Obscure was the novelist’s swan song. Early in 2008 the Fitzwilliam Museum was offered the proofs for the first book edition, substantially annotated by Hardy in 1895. When examined side by side with the autograph manuscript, they reveal the importance of Jude the Obscure for the understanding of Hardy’s creative process as well as the study of literary censorship and social history. The Museum committed all that was available from its slender purchase funds and Friends’ subscriptions, and was fortunate to secure generous donations from private individuals and charitable organisations. Of the £176,000 needed for the purchase only £20,000 remain to be raised in order to unite the proofs with Thomas Hardy’s original manuscript of Jude the Obscure.

John Linnell (1792-1882)

The Museum owes its rich holdings of works by William Blake to Sydney Cockerell. His interest in Blake was awakened in the 1890s by the poets in his new circle of friends, notably W.B. Yeats. The Pre-Raphaelites admired Blake. In 1868 Swinburne had published his essay William Blake, exalting the artist’s spiritual and visionary genius, and had presented a copy to Blake’s other great champion, Rossetti. This copy came to the Fitzwilliam in 1913 as a gift from Murray Marks. Around 1864 Rossetti had lent a copy of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell to Swinburne who made a transcription for himself of what he considered Blake’s crowning achievement as a prophet. In 1916 Cockerell extracted Swinburne’s manuscript from Charles Fairfax Murray who had presented The Book of Thel issued by Blake in 1789 four years earlier. In 1910 Cockerell had organised an exhibition of Blake’s works based entirely on loans. He also made shrewd purchases, using the Friends’ subscriptions.

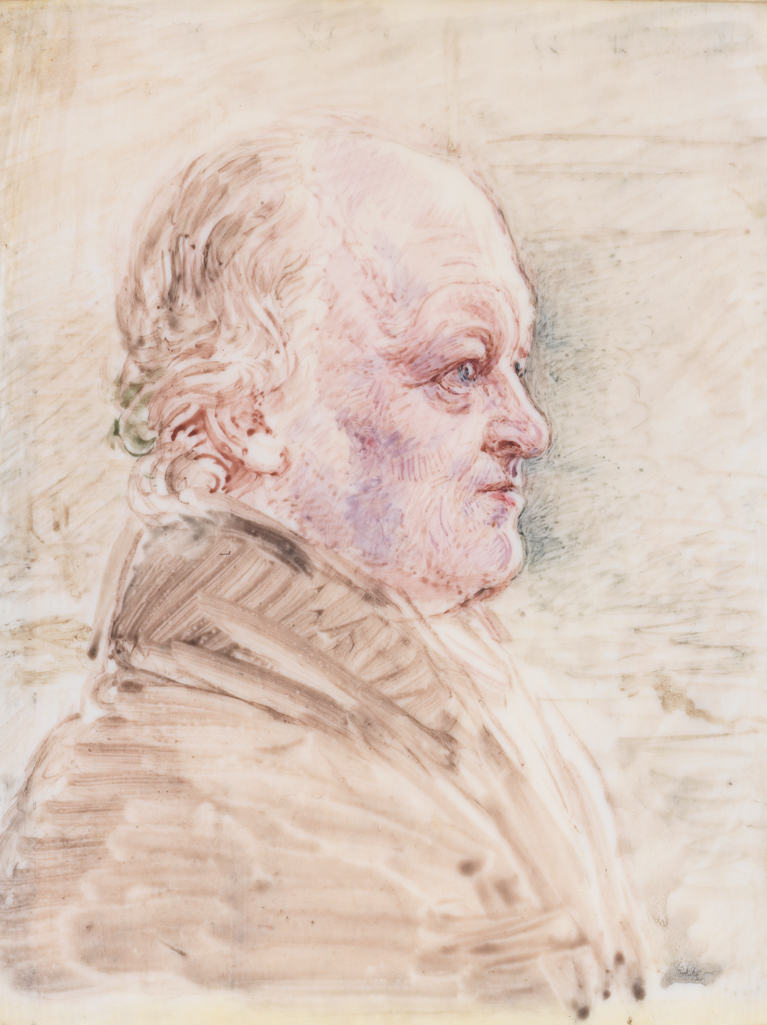

Cockerell’s most generous donors of Blake material were Thomas Henry Riches and his second wife, Katherine A. Linnell. She was the granddaughter of John Linnell, William Blake’s friend, last great patron, and commissioner of the series of watercolours for such major works as The Book of Job, Dante’s Divine Comedy and Milton’s Paradise Lost. Katherine Linnell had inherited a valuable Blake collection and was keen to develop it further. In 1918, at the major sale of Blake material that had belonged to John Linnell, the Riches ‘obtained the cream of the collection.’ Some of it was presented to the Fitzwilliam Museum immediately, while the rest came with their entire art collection bequeathed in 1935. It included Linnell’s portrait of Blake and copies of the Songs of Innocence and Experience showing the gradual development of Blake’s painting technique.

Among the first friends to congratulate Cockerell on the Riches bequest was the Blake scholar and collector Geoffrey Keynes. His own bequest would enrich the Museum’s holdings with watercolours, drawings, prints and illuminated books, including copies of Jerusalem, The Book of Job, Songs of Innocence and Experience, and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Although it came in 1985, it was due largely to his friendship with Cockerell, which began as soon as the new Director arrived in Cambridge and continued until his death. Together with Mrs Riches, Geoffrey Keynes was among the first to lend Blake material to the Fitzwilliam in 1910. His first gift to the Museum in 1922 was his Bibliography of William Blake published for the Grolier Club. Ten years after Cockerell’s retirement, he and Geoffrey Keynes were still pursuing Blake’s prints and drawings around the salerooms. As Cockerell had hoped, they joined the Museum’s collection upon Geoffrey Keynes’s death. The Director would have been delighted had he anticipated another major acquisition. In 1999 the Museum purchased the vast archive of John Linnell. Although it contains no drawings or prints, it preserves crucial documentary evidence for the last, most mature period in William Blake’s career.

Samuel Palmer

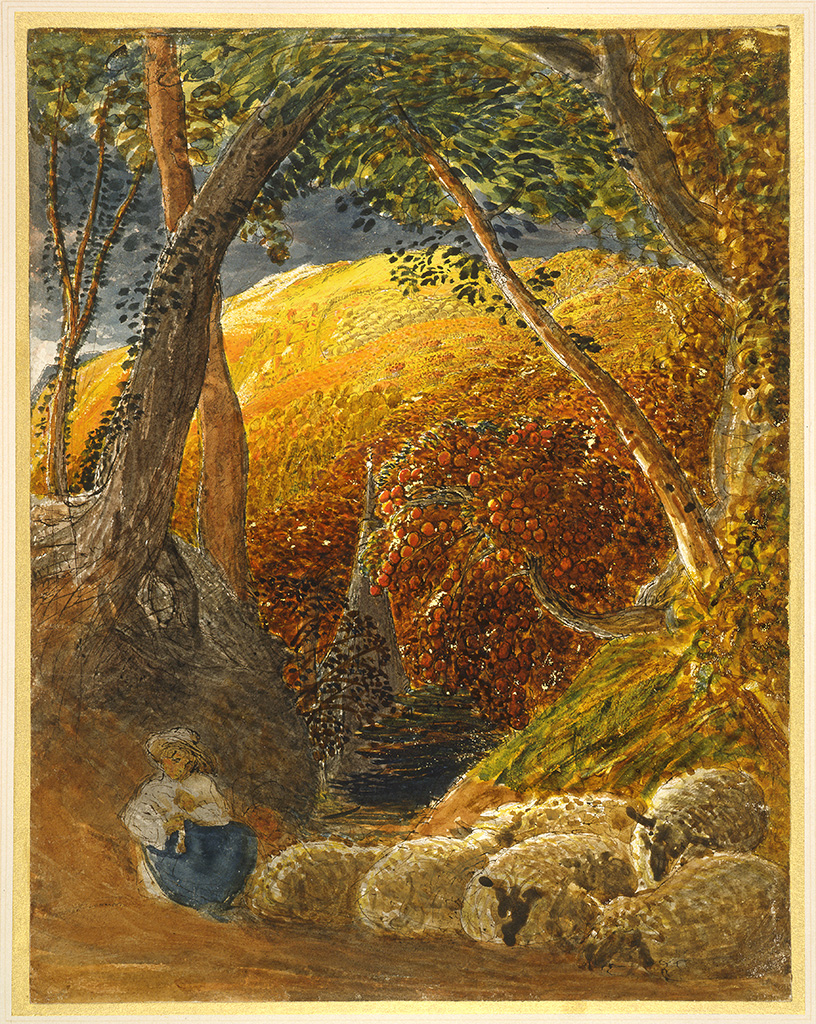

Thanks to Cockerell, the Museum’s collection also represents William Blake’s profound influence on the circle of young poets and artists who considered themselves his faithful disciples and came to be known as the Ancients. Foremost among them was Samuel Palmer who had met Blake in 1824 and had married John Linnell’s daughter in 1837. Palmer’s religious beliefs, ascetic leanings, devotion to Blake and intense reading of poetry inspired a series of visionary landscapes that celebrated the mystical union of art, literature and nature. One of the most famous, The Magic Apple Tree, was presented to the Fitzwilliam by A.E. Anderson in 1928.

Cockerell admired the works of William Blake and Samuel Palmer. They embodied the perfect amalgam of art and poetry that the Pre-Raphaelites strove to achieve and Cockerell considered the ultimate triumph of the creative spirit. He was particularly interested in Blake’s illuminated books, especially the Songs of Innocence and Experience which showed the final stage in their development. While the early copies of Songs of Innocence, issued alone between 1789 and 1794, were coloured in light, delicate washes, from 1794 onwards Blake published them as part of the Songs of Innocence and Experience, raised the number of plates to fifty-four, and in later years painted them in increasingly strong, bold colours, using deeply saturated pigments and gold ink. The Magic Apple Tree, bright and luminous, was Palmer’s response to this final stage in the evolution of Blake’s colour scheme. To Cockerell this spelled the revival of medieval illumination. Indeed, John Linnell had encouraged Blake to look at medieval manuscripts for models and inspiration just as Cockerell urged his most generous donors of Blake material, the Riches, to enlarge their collection of illuminated manuscripts.