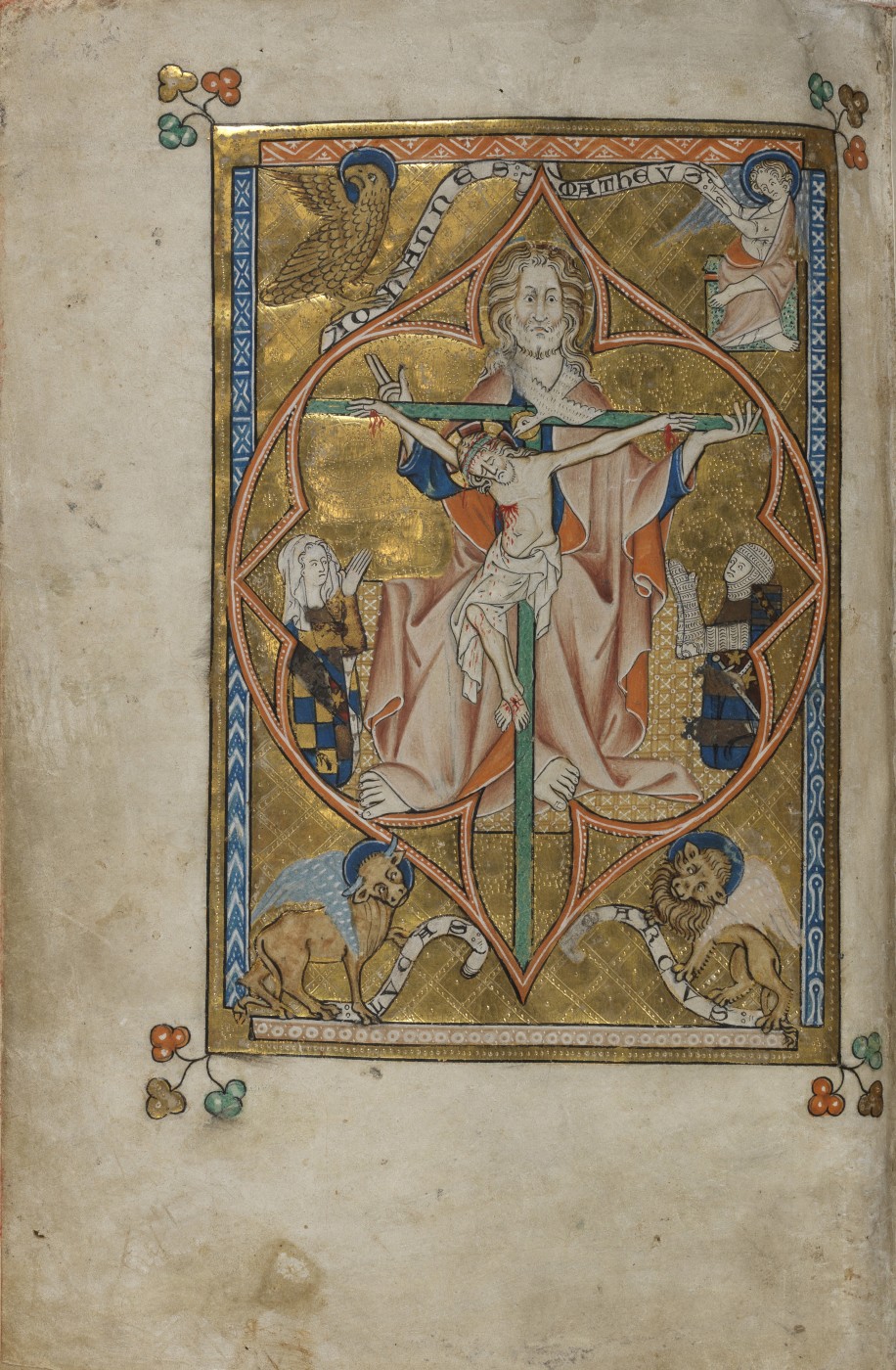

The Pabenham-Clifford Hours

n 22 October 1896 Sydney Cockerell visited Cambridge for the very first time. He came to deliver one of William Morris’s most cherished medieval illuminated manuscripts to the Fitzwilliam Museum. It was the Pabenham-Clifford Hours, made as a wedding gift for the young man and woman depicted in their heraldic dress at major openings. The margins teem with coats of arms, advertising the couple’s feudal alliances, and with scenes from fables, games and hunting, all emblems of their favourite pastimes. As soon as he bought the manuscript in 1894, Morris learnt that two of its leaves had been cut out in the eighteenth century and after various peregrinations had been donated to the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1892.

He wrote to the Director, Montagu Rhodes James. Morris and James were keen to see the leaves re-united with the manuscript, but where was the restored treasure to live afterwards? They struck a deal. The Museum gave Morris less than half of what he had paid at the sale and he was allowed to enjoy the Hours, complete with the two Fitzwilliam leaves, for his lifetime. It was agreed that upon his death the manuscript would come to Cambridge. William Morris died on 3 October 1896 and three weeks later Sydney Cockerell brought the Hours to his predecessor at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

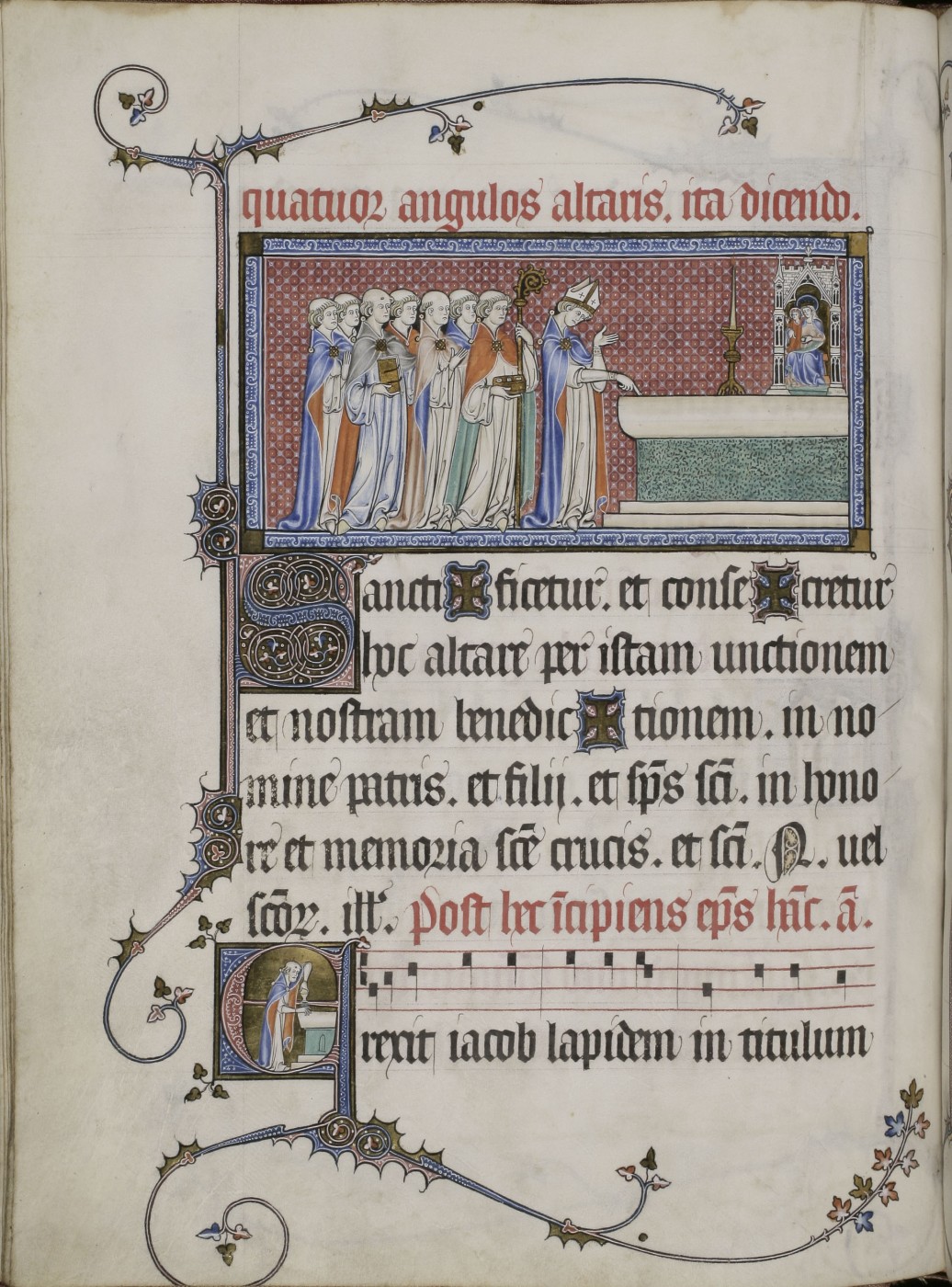

The Metz Pontifical

Cockerell met Henry Yates Thompson in 1896 when he visited Kelmscott House after William Morris’s death, hoping to acquire some of his medieval manuscripts. The eldest son of a Liverpool banker, Yates Thompson had inherited a valuable library and by 1892 had started assembling a fine collection of illuminated manuscripts. He needed help with their cataloguing and in 1898 asked Cockerell to join other scholars working on his collection, notably M.R. James. Cockerell was excited: ‘I am once more revelling in old manuscripts, many of them of the utmost beauty.’ As a Cambridge alumnus, Yates Thompson was a generous patron of his college, Trinity, as well as of Newnham, the University Library, and the Fitzwilliam Museum. Cockerell believed that he would leave his manuscripts to Cambridge.

In December 1917 Yates Thompson ‘horrified’ him with the news that his collection was to be sold at auction. Cockerell poured out his ‘sorrow and dismay’ in a long letter, accusing, promising and pleading.

‘I regard the Fitzwilliam Museum as an ideal destination for such a collection as yours - by reason of its being already recognised as a place offering singular advantages to students of manuscripts, because bequests to it are free of legacy duty, and because of the lucky chance that I can undertake for myself and my successors to build a handsome and suitable room for its permanent exhibition in cleaner air than that of London - and I think that the Fitzwilliam Museum has some claim to your favourable consideration, seeing how largely your manuscripts have been elucidated by two of its Directors.’

It all fell on dead ears, but Yates Thompson sweetened the pill by promising Cockerell the Metz Pontifical, ‘if you become reasonable and not too purely Cockerellian.’

Made for Renaut de Bar, Bishop of Metz (1303-1316), the Pontifical was one of the finest fourteenth-century French manuscripts in private hands. Cockerell brought it to the Fitzwilliam on 10 January and put it ‘in the case that was awaiting it - the most splendid single acquisition that has come to us during my directorship.’ He made announcements in the press and on 3 February the public flocked to the Museum to see the newly acquired treasure. The illumination at the end of the volume was left incomplete, probably at Renaut’s death, and offers fascinating insights into the making of a medieval manuscript.

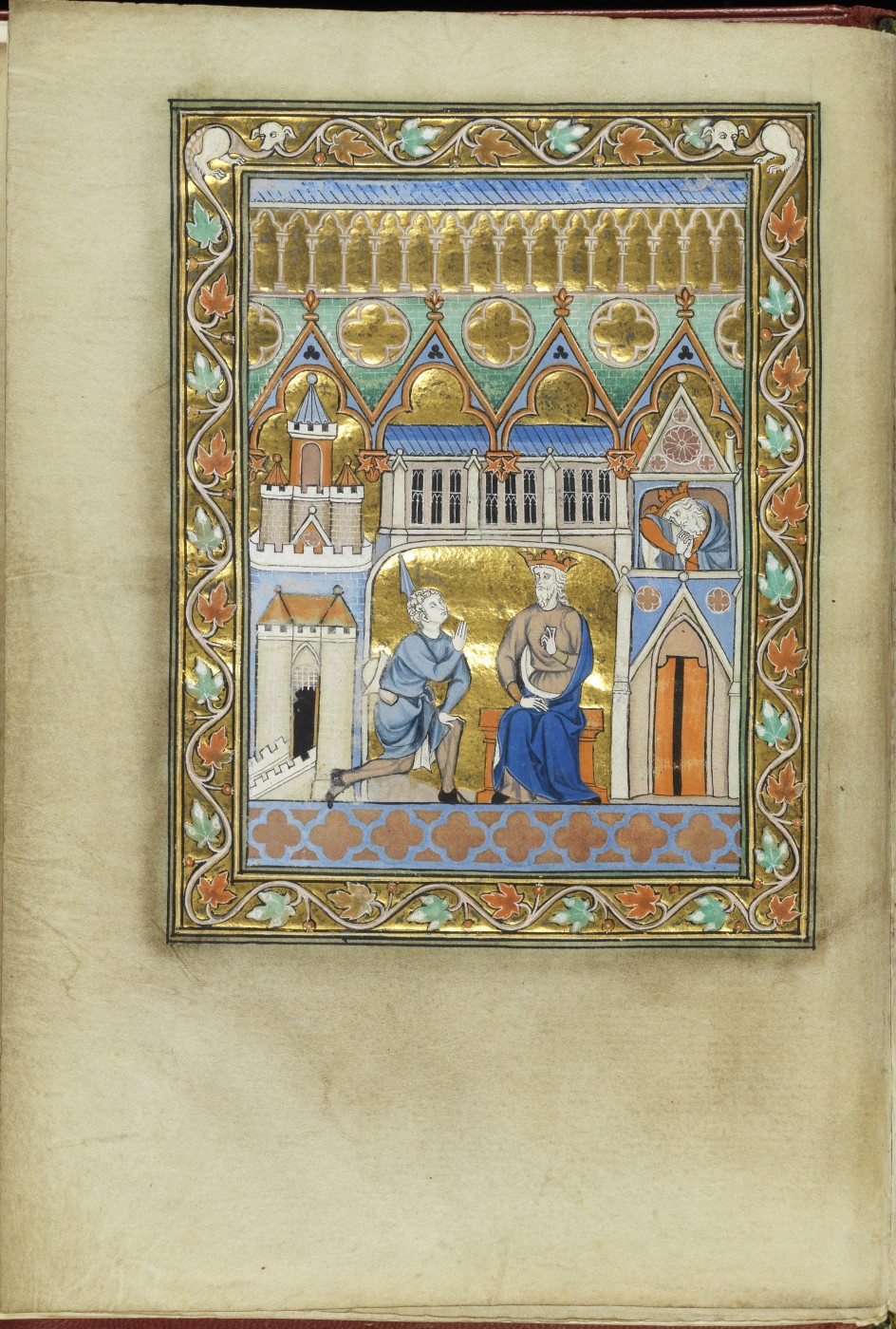

The Psalter-Hours of Isabelle of France

This manuscript is among the finest achievements of the artists, scribes and patrons who transformed thirteenth-century Paris into the leading European centre of manuscript production. It was probably made for Isabelle of France, the devout sister of Louis IX, the Crusading king who built Sainte Chapelle. Cockerell admired it while visiting John Ruskin who had bought it in 1854 as ‘the greatest treasure in all my life.’

This did not stop him from cutting out leaves and using them for teaching or sending them to friends as far as Harvard. Between 1900 and 1903 Cockerell managed to recover the dispersed leaves and buy the volume, then known as the ‘St Louis Psalter’, for Henry Yates Thompson. In 1905 he published his first monograph on the manuscript, establishing that it was made for St Louis’ sister, Isabelle.

Having relinquished hope of salvaging Yates Thompson’s other manuscripts, Cockerell focused on Isabelle’s Psalter-Hours:

‘After turning the matter over and over in the night, I decided that it would break my heart to let the Isabella MS go to America, and that I would sooner sell some of my MSS and give it myself to the Museum.’

But Thomas Henry Riches, whom Cockerell had met in 1904 and transformed into one of the Fitzwilliam’s most generous patrons, lent him £4,000. Cockerell paid Yates Thompson, collected the manuscript and launched the most ambitious campaign of his directorship.

In a speech he gave at a fundraising dinner in July 1919 he compared the price to that ‘of a Rolls Royce motorcar, of four of the finest mezzotints, of three of the rarest postage stamps, of a few Academy pictures, a price bearing no relation whatever to the intrinsic value of the book.’ He shared the news of his success with Thomas Hardy who replied: ‘How you managed to squeeze £1000 out of a dinner table passes my understanding. It is, I admit, better than big game shooting.’ Cockerell raised the rest from sixty-five members of Cambridge University. The last £500 was secured in October 1919 over dinner with J. Pierpont Morgan who had just received an honorary degree and qualified as a member of the University. Cockerell announced that the manuscript, which was ‘without an exact counterpart in any British collection’, would be ‘one of the chief treasures of any Museum or Library in the world.’

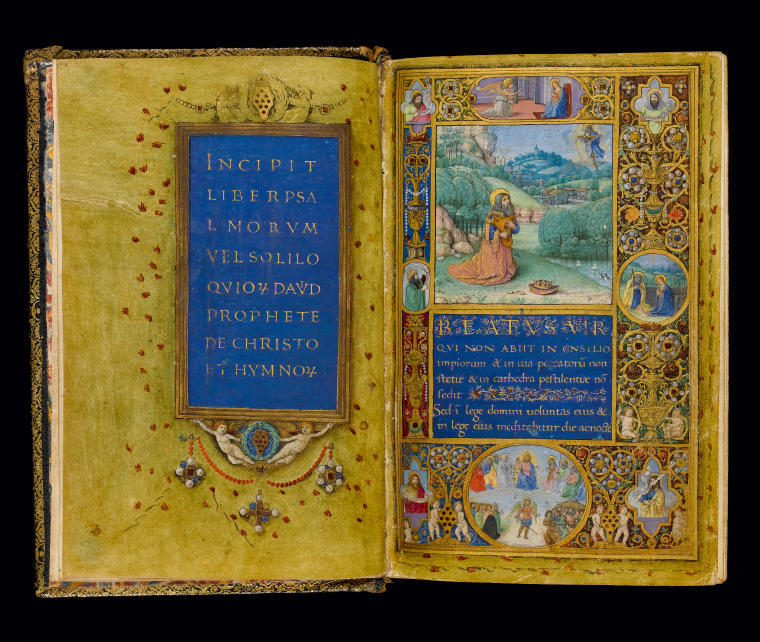

Antonio Sinibaldi (1443-1528) and Gherardo di Giovanni del Fora (1446-1497)

This manuscript was made for a member of the Medici family, as revealed by the ostentatious display of Medici arms and devices. The commission brought together the distinguished Humanistic scribe Antonio Sinibaldi and one of the most versatile artists in late fifteenth-century Florence, Gherardo di Giovanni del Fora. The Medici book was among the seven manuscripts purchased by Thomas Henry Riches at the Yates Thompson’s sales in 1919-1921 and bequeathed to the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1935. While managing the public campaign for Isabelle’s Psalter-Hours, Cockerell was urging the wealthiest collectors among his friends, Thomas Riches and Alfred Chester Beatty, to bid for Yates Thomspon’s deluxe manuscripts in the hope that their purchases would ultimately join the Fitzwilliam’s collections.

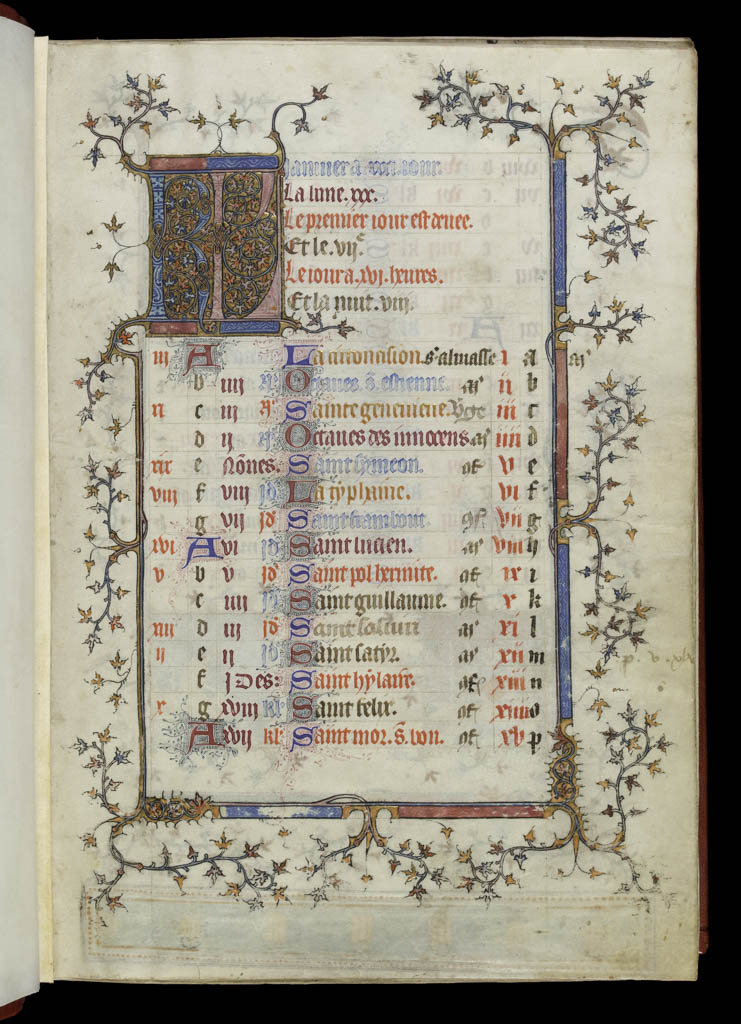

The Hours of Philip the Bold and Philip the Good

This exceptionally rich and complex manuscript belonged to the two most celebrated Dukes of Burgundy. Philip the Bold (1363-1402) commissioned it in Paris in 1376 from the royal scribe Jean L’Avenant and two of the leading Parisian artists. It was only completed in 1451 for his grandson, Philip the Good (1419-1467), who added miniatures by sixteen more artists and inscribed himself into the Burgundain dynastic tradition by creating his private gallery of contemporary painting and a monument of his artistic patronage.

Although the Grandes Heures featured in the fifteenth-century inventories of the Burgundian Library, it vanished from sight until 1939 when Sydney Cockerell rediscovered it in the possession of Mrs Streatfield, wife of the rector of Symondsbury in Dorset. In 1940 she sold it to Viscount Lee of Fareham, a retired politician, collector, and patron of the arts. He had restored Chequers, the Elizabethan house in Buckinghamshire, and given it as a holiday home to successive Prime Ministers.

He had persuaded Samuel Courtauld to sponsor the foundation of the Courtauld Institute in 1932 and negotiated with M.I.5 the transfer of the Warburg Institute from Hamburg to London in 1933. Cockerell who had known Lord Lee, his collections and his influence in the corridors of power since the 1920s, remained in touch with him after his retirement. Although Lord Lee sent his silver and manuscripts to the University of Toronto for safekeeping during WWII, he reclaimed the five most sumptuous volumes after the war. The two that he managed to recover were bequeathed to the Fitzwilliam together with his later acquisitions, including the Grandes Heures.

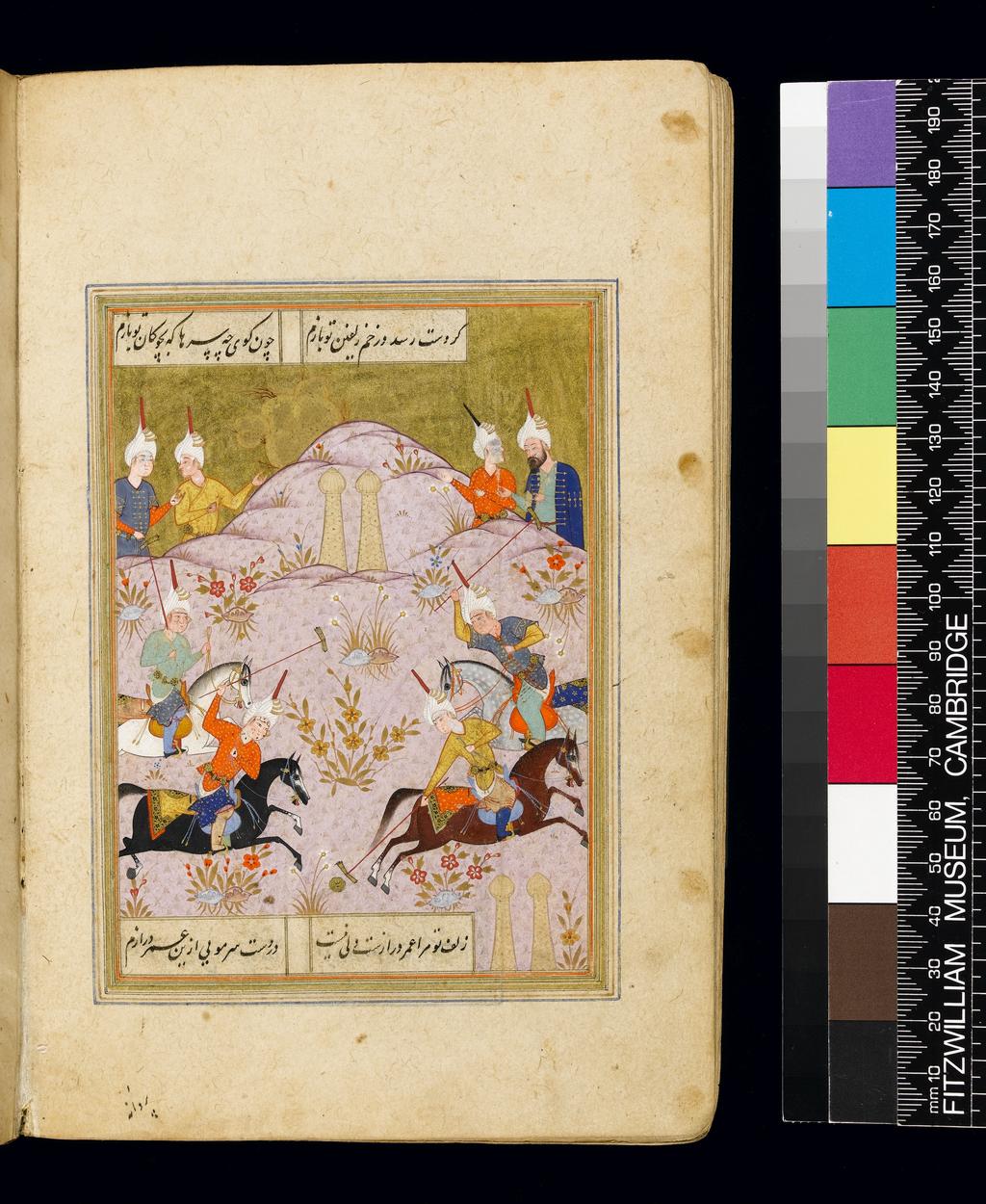

Firdausi, Shahnama

The Shahnama, the Persian ‘Book of Kings’, was completed in 1010 by the poet Abu’l-Qasim Firdausi of Tus, in Northeast Iran. The great epic poem captures the history and living legends of Iran, from the earliest times to the fall of the Persian Empire in the seventh century. This manuscript was made in 1621 in Astarabad, in the Caspian region of Northern Iran. The miniature shows the Iranian Prince Siyavush, who had fled from his father, being welcomed at the rival Turanian court of king Afrasiyab. Cockerell’s curiosity about the literature and arts of the East was first aroused by William Morris who cherished his Persian pottery, rugs and illuminated manuscripts, including this copy of the Shahnama. After Morris’s death the manuscript was acquired by Wilfrid Blunt under whose influence Cockerell’s early fascination with the splendours of the Orient developed into a life-long passion. In addition to this volume and his private papers, Blunt bequeathed £45 for the purchase of another Persian manuscript.

Hafiz, Diwan

Perhaps the best-loved medieval Persian poet, Hafiz lived during the most turbulent years of the fourteenth century, between the rule of Chingiz Khan and the arrival of Tamerlane. Echoing Koranic verses, the intricate poems of his Diwan sport abrupt twists from jest to seriousness and from lyricism to mysticism. An unsurpassed masterpiece of Persian poetry, the Diwan was a high priority for Cockerell and a purchase that would honour Wilfrid Blunt’s bequest. He identified a highly desirable copy in the collection of Alfred Chester Beatty, the American engineer who had amassed a considerable fortune from his international mining business and was already buying manuscripts, both Western and Oriental, when Cockerell met him in 1916. While helping him acquire exceptional works, Cockerell persuaded Chester Beatty to join the Friends of the Fitzwilliam Museum and to lend four of his finest Persian manuscripts in 1919. In 1928 Chester Beatty ceded the Diwan for £45, a price considerably lower than the current market value, and agreed to forgo payment, allowing Cockerell to use the sum in lieu of his annual subscription to the Friends. The Director acknowledged the purchase of the Diwan from the Blunt Fund with ‘generous cooperation’ from Chester Beatty. Effectively, he received the manuscript for free.

Florence Kingsford (d.1949)

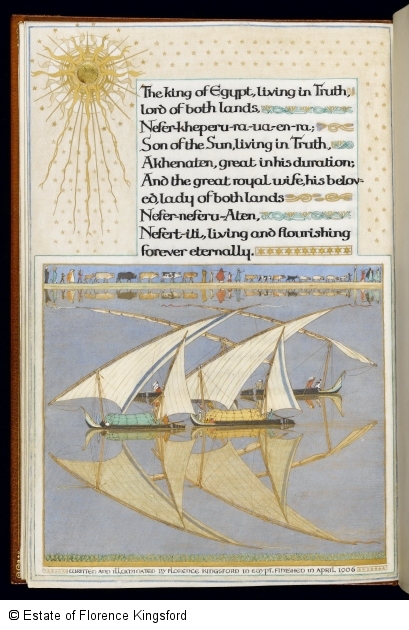

Cockerell’s statement ‘I haven’t a spark of imagination, and am only good for dry-as-dust cataloguing’ is understandable, given the numerous artists and diverse talent that surrounded him. But calligraphy was the one medium to which he applied both his imagination and his hand. He confessed that he ‘was interested in handwriting almost from the cradle’ and his neat, minute hand graced his diaries and voluminous correspondence until his death at the age of 94. His interest in calligraphy developed under the influence of William Morris and Florence Kate Kingsford whom he met in 1900 and married in 1907. A student of Edward Johnston, the eminent scribe and designer whose career Cockerell claimed to have launched, Kate completed some sixty works, mostly between 1900 and 1910. After that, her growing family and deteriorating health (she endured heroically the developing multiple sclerosis) left little time and energy for her books.

Concerned about her chronic poverty, Cockerell ensured that Kate charged adequately for her work and found her commissions from wealthy patrons. He was deeply sympathetic of the appalling conditions in which she lived while working for Flinders Petrie in 1905-1906, making drawings of his finds in Egypt. It was in Egypt in 1906 that Kate completed what Cockerell considered her highest achievement, the manuscript of Akenaten’s Hymn to Atten the Sun-Disc.

‘The Nile picture is the best thing Miss K. has ever done… I think it a work of genius’, he wrote in September 1906 to his friend Katie Adams who bound most of his manuscripts, including Kate’s works. On 28 October 1906 Cockerell told Kate that the Hymn to Atten had arrived safely in its new binding by Katie Adams and had ‘made a great sensation… The Lyttons are here & also count themselves among your enthusiastic admirers… The Nile picture is hailed as a great masterpiece.’ Later on Cockerell displayed Kate’s calligraphy at major venues, including the Louvre in 1914, and after her untimely death in 1949 prepared a catalogue of all her works in his possession.